Description

YACHT REGISTRATION VS DOCUMENTATION

Documentation has some advantages, but it’s not right for every yacht out there.

Should you document your yacht with the federal government, or does it make more sense to simply register the vessel in your state? Maybe both are in order? Each state has different requirements for registration, and they all have different agencies responsible for management. So you’ll need to figure out the ins and outs of registering in your own state. And if you find there are more outs than ins, it might be time to consider documenting with the federal government.

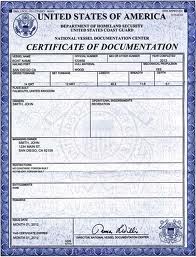

Documenting vessels started as a way for the government to manage commercial shipping. Today, the U.S. Coast Guard is in charge of documentation and there are multiple types of vessels that can be documented—including recreational vessels. Any documented vessel may be used for recreational purposes, regardless of its endorsement, but a vessel documented with a recreational endorsement only may be used for that purpose. If you want to run a commercial fishing charter business on your boat, for example, you’ll have to document your vessel with a fishing designation even if you also use it for pleasure.

Any vessel of five net tons or more can be documented. Net tonnage is a measure of a vessel’s cargo carrying volume. It should not be confused with the vessel’s weight, which may also be expressed in tons. Most vessels more than 25 feet in length will have a cargo volume of five net tons or more.

Documented vessels are given unique official numbers similar to state registration numbers. However, documented vessels don’t display their official numbers on the outside of the hull, like a state registration, but instead, are identified by the name and hailing port. The official number is placed inside. The application for documentation must include a name for the vessel, which may not exceed 33 characters. The name may not be identical, actually or phonetically, to any word or words used to solicit assistance at sea; may not be obscene, indecent, or profane; and may not use racial or ethnic epithets. Once established, a vessel’s name may not be changed without filling out an application and paying more fees.

Why would you want to document your yacht? First, in some cases, it may eliminate the need for state registration (though you’ll usually still have to pay the state the same taxes; this isn’t a “dodge”). More importantly for long-distance cruisers, if you travel to foreign waters, the Certificate of Documentation facilitates clearance with foreign governments and provides certain protection by the U.S. flag. Plus it may be easier to get a bank loan to finance your vessel if it’s documented. The bank is interested in recording a “First Preferred Ships Mortgage” to perfect their lien, and this document is enforceable throughout the U.S., its territories, and some foreign countries. There may also be some tax savings, but you’ll need to check with your state to find out the preferred tax status for documented vessels. The one-time documentation charge is $133.00, versus recurring annual state fees which are often based on a sliding scale using boat length. Remember, however, that documentation doesn’t carry over to dinghies or tenders—these still need to be registered with the appropriate state.

Documentation can also make it easier to travel up and down the coast of the US. Most states allow boats registered in other states to “visit” their waters for a period of time without obtaining registration. But if you plan to take your boat to another state for more than a couple of months, the state you’re visiting may want you to register there; unless you stay long enough to be considered a resident, documented vessels may avoid this fineable situation.

Once documented, your boat or yacht stays documented for its life. This means that if you sell it, the new owner needs to update the documentation information (along with a fee, of course) and the vessel’s documentation ID number, which needs to be affixed to the interior, stays the same. There is an annual documentation update form required by the Coast Guard, but this is automatically sent out to you 45 days in advance of annual expiration, and there are no further fees involved.

If you sell a documented vessel, you do need to return the current Certificate of Documentation to the National Vessel Documentation Center along with a note that you sold the vessel. Your existing Certificate is nontransferable and should not be given to the new owner. You also have to complete a US Coast Guard Bill of Sale (CG-1340), that can be used by the new owner should he or she wish to continue to document the vessel. Since documentation also tracks liens and mortgages, the mortgagee (lender) completes a Satisfaction of Mortgage form and mails an original and one copy to the National Vessel Documentation Center. Your vessel can’t be removed from documentation with an outstanding mortgage.

So, does documentation sound like the better path? You can get assistance from your Nautical Consulting if you like, but in truth, the documenting process is no more complex than most state registrations. For more information on documenting your boat contact the National Vessel Documentation Center.

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.